Map

Summary

On December 12, 2013, a United States aerial drone launched four Hellfire missiles on a convoy of 11 cars and pickup trucks during a counterterrorism operation in rural Yemen. The strike killed at least 12 men and wounded at least 15 others, 6 of them seriously.

Yemen authorities initially described all those killed in the attack outside the city of Rad`a as “terrorists.” The US government never officially acknowledged any role in the attack, but unofficially told media that the dead were militants, and that the operation targeted a “most-wanted” member of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) who was wounded and escaped.

Witnesses and relatives of the dead and wounded interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Yemen said the convoy was a wedding procession. They said everyone in the procession was a civilian, including all of the dead and injured, and that the bride received a superficial face wound.

After the attack, angry residents blocked a main road in Rad`a, a provincial capital in central Yemen, while displaying the bodies of those killed. Provincial authorities then unofficially acknowledged civilian casualties by providing money and assault rifles—a traditional gesture of apology—to the families of the dead and wounded.

Human Rights Watch found that the convoy was indeed a wedding procession that was bringing the bride and family members to the groom’s hometown. The procession also may have included members of AQAP, although it is not clear who they were or what was their fate. However the conflicting accounts, as well as actions of relatives and provincial authorities, suggest that some, if not all those killed and wounded were civilians.

This raises the possibility that the attack may have violated the laws of war by failing to discriminate between combatants and civilians, or by causing civilian loss disproportionate to the expected military advantage.

Neither the US government nor the Yemeni government has offered specific information that those whom the eight relatives and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch listed as killed and injured were involved in militant activities.

The legality of the December 12 attack hinges on both the applicable body of international law and the facts on the ground. If international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, applies to the December 12, 2013 attack, only valid military objectives such as AQAP leaders or fighters could have been lawfully targeted. The burden is on the attacker to take all feasible precautions to ensure that a target is a combatant before conducting an attack and to minimize civilian harm.

Had AQAP members deliberately joined the wedding procession to avoid attack they would have been committing the laws-of-war violation of using “human shields.” AQAP shielding would not, however, justify an indiscriminate or disproportionate attack by US forces.

The United States should carry out a prompt, impartial and transparent investigation into the attack, hold those responsible to account for any wrongdoing, and provide appropriate compensation. US officials speaking on condition of anonymity told media they are investigating the incident, but Human Rights Watch has found no evidence of an inquiry.

The December 12 attack also raises serious questions as to whether US forces are complying with the policy requirements on targeted killings that President Barack Obama outlined in May 2013. Before any such strike, the president said, the United States must have “near-certainty” that no civilians will be harmed.

In refusing to acknowledge any role in the strike, the United States has also failed to demonstrate that the alleged target was present, could not feasibly have been arrested, or posed a “continuing and imminent threat”—three other US policy requirements.

Rather than instilling confidence that its attacks are lawful and adhere to US policy, the silence of the Obama administration on strikes such as the one on the December 12 wedding procession instead magnifies the concerns. The failure to publicly acknowledge and investigate attacks causing civilian casualties not only violates the international legal obligations of the United States, it also shows an unwillingness to address the harms inflicted on Yemen’s civilian population.

Recommendations

To the Governments of the United States and Yemen

- Ensure that the United States is taking all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians in targeted killings and is complying with all other obligations under the laws of war. Outside of armed conflict situations, use lethal force only when absolutely necessary to protect human life in accordance with international human rights law.

- Conduct prompt, thorough, and impartial investigations into the air strike outside Rad`a on December 12, 2013 and other strikes that may have violated the laws of war. Make public the findings, including drone videos of the attack, and seek disciplinary measures or criminal prosecutions as appropriate.

- Implement a system of prompt and meaningful compensation for civilian loss of life, injury, and property damage from unlawful attacks. The United States also should institute a system of condolence or ex-gratia payments, as it has done in Iraq and Afghanistan, for losses in which there is no assumption of liability.

To the US Government

- Explain the full legal basis on which the United States carries out targeted killings, including the attack on December 12, 2013.

- Publicly clarify all policy guidelines for targeted killings. Explain the apparent discrepancy between the strike on December 12, 2013 and the May 2013 policy on targeted attacks announced by President Obama on May 23, 2013.

Human Rights Watch’s full set of recommendations on targeted killings in Yemen can be found in “Between a Drone and Al-Qaeda”: The Civilian Cost of US Targeted Killings in Yemen (2013).

Methodology

This report is based on research by Human Rights Watch in Sanaa, Yemen, from January 11 to 16, 2014. The research included interviews with more than 25 people including eight relatives of those killed or wounded in the December 12, 2013 attack, two of whom witnessed the strike and two of whom came to the scene immediately after. Those interviewed also included Yemeni civil society activists and journalists who visited the strike area, as well as Yemeni government officials and Western diplomats. Security concerns prevented Human Rights Watch from visiting the strike area.

Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews in New York and Washington, DC, and reviewed photos and video footage of the strike aftermath, as well as Yemeni and international media accounts of the incident.

Human Rights Watch carried out interviews in English or in Arabic, often with interpreters. We informed the interviewees of the purpose of our research and did not pay them or offer them other incentives to speak with us. In some cases, we have withheld the name, location, date of interview, or other identifying information to protect the interviewee from possible retaliation. US and Yemeni government officials spoke to us on condition of anonymity.

This report also draws on material from the 2013 Human Rights Watch report “Between a Drone and Al-Qaeda”: The Civilian Cost of US Targeted Killings in Yemen (2013).

I. US Targeted Killings in Yemen

“Targeted killings” have been defined as deliberate lethal attacks under color of law, by government forces or their agents, against a specific individual not in custody.[1] Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States has carried out targeted killings in Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia, and possibly other areas outside conventional battlefields, most often with remotely piloted aerial vehicles known as drones.

The United States has conducted at least 86 targeted killing operations in Yemen since 2009, killing some 500 people, according to research groups that track the attacks.[2] These strikes have been carried out by either the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), an elite, quasi-covert arm of the US armed forces.[3] The main target in Yemen is Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which President Barack Obama has called Al-Qaeda’s “most active and dangerous affiliate.”[4]

US officials began acknowledging targeted killings in 2010. But, citing national security concerns, they have provided almost no information on individual strikes, including casualty figures. Nor have they detailed an adequate legal rationale for these killings.[5]

In an October 2013 report, Human Rights Watch examined six US targeted killings in Yemen from 2009 to 2013 and found two of the strikes indiscriminately killed civilians, a serious violation of the laws of war. We found possible laws-of-war violations in the other four.[6]

Human Rights Watch also found that the operations did not comply with the targeted killing policies that President Obama outlined on May 23, 2013: that the United States must have a “near-certainty” that a target is present who poses a “continuing and imminent threat,” that capture is not feasible, and that no civilians will be harmed.[7] Unlike the attack documented in this report, it is unclear whether the policies were in effect when those strikes took place; the United States will not disclose when it implemented them.

Yemen’s President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi has repeatedly told media that he approves each US strike.[8] However, in a meeting with Human Rights Watch on January 28, 2014, the president did not confirm Yemen’s approval at the actual time of the strike. Rather, he said, the strikes are “generally permitted” pursuant to an agreement that then-president Ali Abdullah Saleh signed with the United States after the 9/11 attacks, to which President Hadi said he is bound.[9]

A Yemeni government official, as well as a senior Yemeni government official under Saleh, told Human Rights Watch they were unaware of any signed agreement between Yemen and the United States on drone strikes.[10] “There is a gentlemen’s agreement,” the current official said.[11] A third Yemeni official said that, “There is coordination between the Yemeni and the US governments, but we don’t really know how things are processed on the American side. This is an area that has to be addressed.”[12]

Hadi also told Human Rights Watch that a “joint operations room” that includes the United States, the United Kingdom, Yemen, and NATO “identifies in advance” the individuals that are “going to be targeted.” The current Yemen government official confirmed the existence of the center but said it was for an array of “intelligence-sharing activities” rather than exclusively for counterterrorism.[13]

Asked about the center by Human Rights Watch, the US and UK governments declined comment and NATO denied any participation. US National Security Council spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden said the United States does “not comment on the specifics of any operational CT [counterterrorism] collaboration that may take place with foreign partner governments.” She also referred Human Rights Watch to President Obama’s comment in his May 2013 speech that, “America cannot take strikes wherever we choose; our actions are bound by consultations with partners, and respect for state sovereignty.”[14]

A UK Foreign Office official said the United Kingdom has a “long-standing policy of not commenting on intelligence issues.” The official added, “Drone strikes are a matter for the US and Yemen, who are facing a shared and dangerous threat from terrorists. There is a need for effective action against terrorism and it is important that Yemen and the international community continue to work together to combat this common threat.”[15]

A NATO official stated that “NATO is not participating in any intelligence, military or counter-terrorism actions inside Yemen” and that “NATO is not involved in identifying Al-Qaeda members in Yemen.” NATO also has no personnel in Yemen, he said. The organization does “infrequently exchange information on naval piracy activity in the region,” the official said.[16]

In response to the December 12 attack, Yemen’s parliament two days later approved a non-binding resolution banning US drone strikes, on which Hadi’s government has not acted.[17]

II. The Attack

|

Residents show a remnant from one of the US Hellfire missiles that struck a wedding procession outside Rad`a, Yemen on December 12, 2013. © 2013 Nasser al-San`a |

The families of the bride and groom feasted on a luncheon of roasted lamb at the home of the bride’s parents.[18] They recited traditional wedding poems and chewed qat.[19] Then many of the men and a small number of women piled into vehicles to escort the newlyweds to a customary second celebration in the groom’s village, a 35-kilometer drive along an isolated mountain road.[20]

Eleven cars, sports utility vehicles and pickup trucks were in the procession, and the mood among the 50 to 60 travelers was festive, said Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, a local sheikh and who was driving one of the vehicles. According to al-Tisi, the gaiety continued even as the recognizable buzz of a remotely piloted drone persisted overhead. “Everyone was happy; everyone was celebrating the wedding,” he said. “Then the strike turned happiness to grief.”[21]

Halfway through the journey, as the procession paused to await a car that had a flat tire, the drone’s volume increased, al-Tisi said.[22] Soon after, at 4:30 p.m., the missiles struck in quick succession. One missile hit the fourth vehicle in the procession, a 2005 Toyota Hilux pickup truck, but not before three or four men inside the pickup had jumped out and fled, apparently alerted by the drone’s increased buzz, he said.[23] Three other missiles hit near the car that was struck, sending shrapnel through four nearby vehicles and killing and wounding passengers inside them.[24]

The strike, on December 12, 2013 in Aqabat Za`j, a district northeast of the central Yemeni city of Rad`a, killed at least 12 men ages 20 to 65 and wounded at least 15 others, according to survivors, relatives of the dead, civil society members, and multiple media reports. The relatives said the dead included the son of the groom from his previous marriage. They said shrapnel grazed the bride under one eye, and blew her trousseau to pieces. [25]

The Washington Post attributed the attack to Hellfire missiles and identified the strike as a JSOC operation.[26] A Human Rights Watch arms expert also identified photos of the remnants as Hellfire missiles.

Conflicting accounts of those killed and wounded quickly emerged. Unnamed US and Yemeni government officials told the media that all those killed were militants, including an AQAP member on Yemen’s most-wanted list. Yemen government sources told Human Rights Watch that civilians were among the dead. (See following chapter.) Relatives interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that all those killed or wounded were civilians.

Rad`a and surrounding tribal lands are largely outside the central government’s control, and AQAP members have frequently staged attacks against Yemeni troops in the area.[27] Nearly everyone in the procession was an adult male, and one Yemeni government source said many of the men carried military assault rifles. But these details do not necessarily point to involvement in violent militancy. Yemeni weddings are segregated, including the traditional journey to bring the bride to her new home. And Yemeni men commonly travel with assault rifles in tribal areas, including in wedding processions, when celebratory gunshots are common.

Al-Tisi, the sheikh, showed Human Rights Watch five scars on his legs, head, and one hand that he described as shrapnel wounds from the strike. He said his son Ali Abdullah, a 36-year-old father of three who had been a soldier, was among the dead:

Blood was everywhere, the bodies of the people who were killed and injured were scattered everywhere…. I saw the missile hit the car that was just behind the car driven by my son. I went there to check on my son. I found him tossed to the side. I turned him over and he was dead. He was struck in his face, neck, and chest. My son, Ali![28]

Survivors took the wounded and the bodies of 11 of the dead to Rad`a, a 35-kilometer, 90-minute drive along a dirt road from the strike area.[29] Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani, a local sheikh, said he received the injured at a Rad`a hospital. He said three men died in the hospital and that six others were seriously wounded, including a man who lost one eye, another who lost his genitals, and others who had lost a leg or hand.[30]

Nasser al-San`a, a journalist from Rad`a, reached the hospital and also counted six seriously wounded men. He showed Human Rights Watch videos he took of several bloodied men at the hospital, as well as charred bodies of the dead.[31]

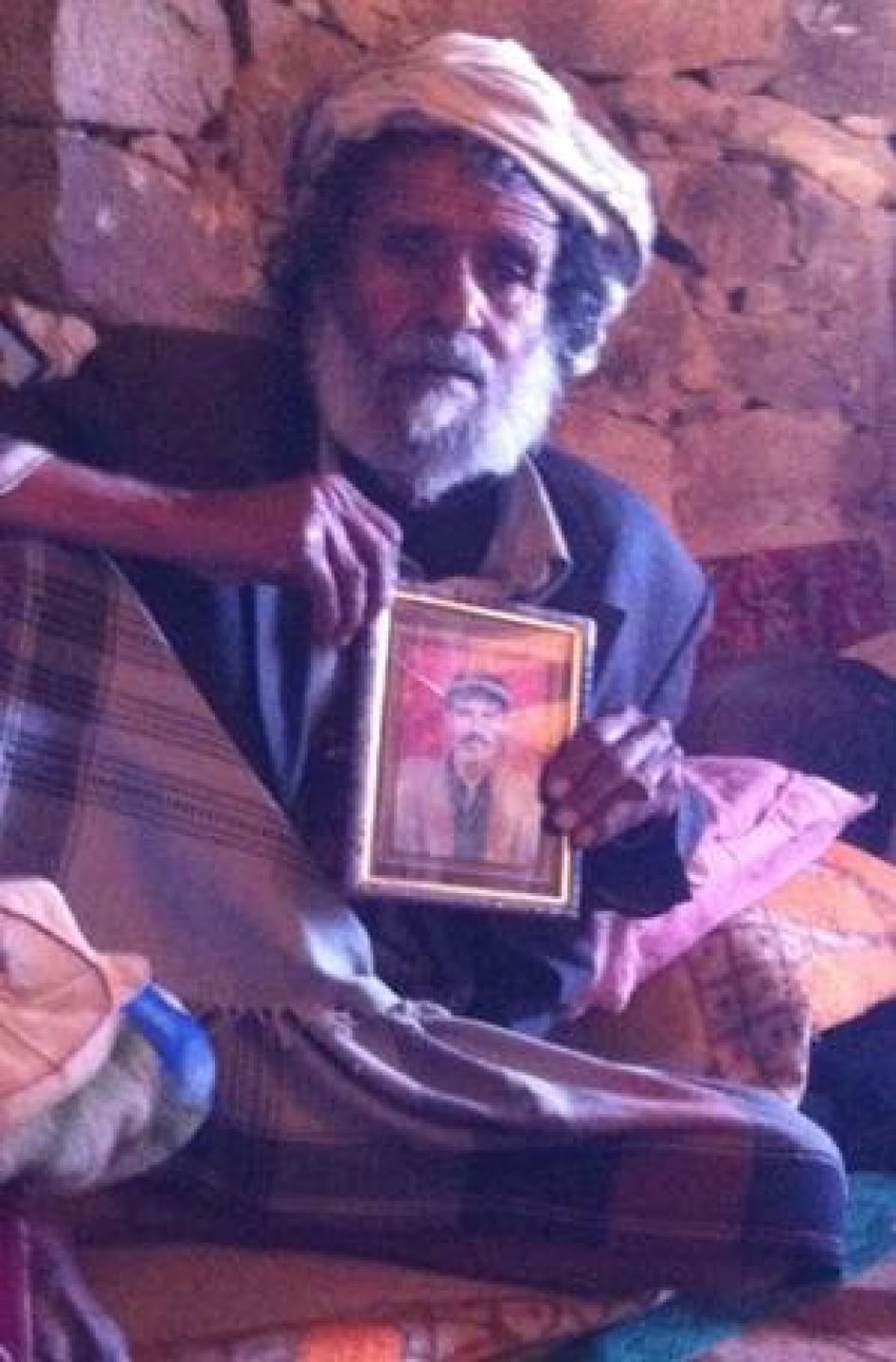

Relatives told Human Rights Watch that all of those killed were from the al-`Amri and al-Tisi families from the Yakla area of al-Bayda province. They said most worked as migrant laborers in neighboring Saudi Arabia, herded sheep, or farmed qat—a substance of which AQAP disapproves. One, `Aref Ahmed al-Tisi, 28, had cared for a blind father, a wife, and seven children, including a son who had been born less than two weeks before his death, according to a relative and al-San`a, who showed Human Rights Watch video footage he had taken of al-Tisi’s father and children after the attack.[32]

Videos of Jishm Yakla, the home village of several of the men killed, showed a barren landscape dotted with stone huts. The village had no electricity or basic services. Another video showed the groom, Abdullah Mabkhut al-`Amri, 60, raising his hands to the sky, and saying:

We were in a wedding, but all of a sudden it became a funeral. …We have nothing, not even tractors or other machinery. We work with our hands. Why did the United States do this to us?[33]

Enraged, relatives and other local residents took the bodies as well as the broken pieces of the bride’s wooden armoire and displayed them in the provincial capital, Rad`a. Armed protesters blocked the main thoroughfare from Rad`a to the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, 150 kilometers northwest, for more than 24 hours.[34]

|

Ahmad Muhammad al-Tisi of Yakla holds a photo of his son `Aref Ahmad Muhammad al-Tisi, 28, who was killed in a US drone strike outside Rad`a, Yemen on December 12, 2013. © 2013 Nasser al-San`a |

Video clips of the protest show angry tribesmen waving banners and chanting slogans denouncing the US and Yemeni governments. “The US is committing bloodshed!” one man shouted. “Who will stand against it?”[35]

Al-Tisi was among several residents who demanded an international investigation into the attack, saying he did not trust the United States to carry out an impartial inquiry:

The US government killed innocent people. This was an immense mistake, rejected by the God and His Prophet. They turned many kids into orphans, many wives into widows. Many were killed and many others injured. … Where is the concern for human rights?

The Dead and Wounded

Relatives provided Human Rights Watch the following lists of the dead and seriously wounded, all from villages in and around Yakla.

The Dead[36]

- Hussein Muhammad Saleh al-`Amri, 37

- Muhammad Ali Mes`ad al-`Amri, 34

- Ali Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, 36

- Zaidan Muhammad al-`Amri, 34

- Shaif Abdullah Mohsen Mabkhut al-`Amri, 22

- Hussein Muhammad al-Tomil al-Tisi, 65

- Motlaq Hamoud Muhammad al-Tisi, 41

- Saleh Abdullah Mabkhut al-`Amri, 30

- `Aref Ahmad Muhammad al-Tisi, 28

- Saleh Mes`ad Abdullah al-`Amri, 30

- Mes`ad Dhaifallah Hussein al-`Amri, 25

- Salem Muhammad Ali al-Tisi, 31

The Seriously Wounded[37]

- Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, 52, multiple shrapnel wounds

- Muhammad Ali Abdullah al-`Amri, 45, multiple shrapnel wounds

- Naif Abdullah Ali al-Tisi, 30, lost vision in one eye, broken leg

- Muhammad Ali Ahmad al-`Amri, 40, lost body parts including part of one leg

- Nasser Ali Ahmad al-`Amri, 36, wounded in the back, leg

- Abdullah Aziz Mabkhot, 30, broken hand and leg

III. The Alleged Target

US and Yemeni officials and relatives provided divergent and often contradictory accounts as to who was killed in the December 12 attack. US officials, speaking to the media on condition of anonymity, said that all those killed were militants. Yemeni government sources gave divergent accounts of civilian and militant deaths. Neither US nor Yemeni officials offered specific information to support their claims of a militant presence, although the laws of war require the attacker to establish that it is striking a valid military target.

Eight family members, In contrast, told Human Rights Watch that none of the people in the procession, including the dead and wounded, was engaged in any militant operations.

These discrepancies underscore the need for a thorough, impartial, and transparent investigation into the strike.

US: All Killed Were Militants

The Associated Press quoted two unidentified US officials as saying said that all those killed in the December 12 attack were militants. [38] The officials said the target was an AQAP member named Shawqi Ali Ahmad al-Badani, whom they described as one of Yemen’s most-wanted terrorists and the ringleader of the plot that temporarily shuttered 22 US diplomatic posts worldwide in August 2013. Al-Badani, they said, was wounded in the attack but escaped. [39] According to a Yemeni official, al-Badani was from the city of Ibb, 180 kilometers southwest of the area of the strike. The official, as well as a Yemeni security analyst, confirmed that al-Badani was on Yemen’s “most-wanted” terrorist list. [40]

The security analyst, Abd al-Salam Muhammad, president of Yemen’s Abaad Studies and Research Center, told Human Rights Watch that al-Badani’s name had surfaced on militant chat sites after the December 12 attack as an “emir [leader] of Sanaa,” but that prior to that date, “most people had never heard of him.”[41]

US officials speaking on condition of anonymity told NBC News that the Obama administration was carrying out an internal review of the strike—a rare if unofficial acknowledgement of any action involving targeted killings.[42] However, the administration had not formally announced an investigation or publicly acknowledged the strike at the time of writing.[43] Nor has it released information, such as the videos that drones take during strikes.

In an email, Caitlin Hayden, a spokeswoman for the US National Security Council, instead referred Human Rights Watch to a statement of the Yemeni government that “those killed were dangerous senior al-Qa’ida militants.”[44]

Citing President Obama’s May 2013 speech on targeted attacks, Hayden wrote that the United States takes “extraordinary care” to ensure its strikes comply with domestic and international law as well as US policy. She added: “And when we believe that civilians may have been killed, we investigate thoroughly”—even though the findings are not public. “In situations where we have concluded that civilians have been killed,” she added, “the U.S. has made condolence payments where appropriate and possible.”[45]

In February 2013, the then-White House counterterrorism chief John Brennan, who is currently the CIA director, also said that the government reviews strikes, and if appropriate and feasible provides compensation, in the “rare instances” in which civilians are killed.[46]

Human Rights Watch has found no evidence of US investigations or payments to families in connection with the December 12 strike.

|

Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri of Yakla shows photos of nephew Shaif Abdullah Mohsen Mabkhut al-`Amri (left) and cousin Saleh Mes`ad Abdullah al-`Amri, who were killed in a US drone strike outside Rad`a, Yemen, on December 12, 2013. © 2013 Human Rights Watch |

Varying Yemeni Accounts

Accounts from Yemeni government officials as to whether civilians were killed in the strike have shifted over time and have often been inconsistent.

The day after the attack, Yemen’s official SABA news agency released a statement that said the strike targeted a car that belonged to an Al-Qaeda “leader” and was carrying “many terrorist members and leaders who were involved in plotting attacks against armed forces, police, and vital public facilities.”[47] The statement, from an unnamed “official source” in the government’s Supreme Security Committee, made no mention of civilian casualties.

However, the following day, December 14, Gen. Ali Mohsen Mothana, commander of a military zone that includes al-Bayda, and al-Ghahiri al-Shadadi, the governor of al-Bayda, apologized for the killings in a public meeting in Rad`a, calling them a “mistake.” [48] The families agreed to no further disruptions for one month in exchange for mediation on their demands to prosecute those responsible for the strike and stop drone flights over their villages. [49] Residents later said that the drone flights stopped for two days, then resumed. [50]

Those at the meeting told Human Rights Watch that the two provincial officials also gave all the families of the dead and wounded a total of 34 million Yemeni rials (nearly US$159,000): 2 million rials ($9,300) for each of the 12 dead and 10 million rials ($46,600) total for the wounded. The officials also gave the families 101 Kalashnikov assault rifles, a tribal gesture of apology. The apology and payment of money and guns also was reported in Yemeni media. [51]

Speaking on condition of anonymity, two senior Yemeni government officials and a ranking official during the Saleh presidency, all with links to defense and intelligence agencies, gave Human Rights Watch accounts that differed from the official statement printed by SABA. The officials said they had been told by their own sources—whom they did not identify—that the dead included civilians, though only one specified a number, five.[52]

While the former official reiterated the official position that AQAP members were targeted in the strike, he also acknowledged that “there is no doubt that it was a wedding convoy and that civilians were killed.”[53]

None of the Yemeni officials specified which of the dead were civilians and which were alleged AQAP members. One of the officials said he was informed that those killed “included smugglers and arms dealers. They were guys for hire—shady.”[54]

Two Yemeni government officials said in separate interviews that according to their sources, the pickup truck that the first missile hit was carrying the alleged AQAP member al-Badani but that he escaped.[55]

The witnesses and relatives with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said al-Badani was not at the wedding or in the procession and that they did not know him. Only close relatives attended the ceremonies, they said. “Whoever says otherwise is a liar,” said one local sheikh, Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani.[56]

One of the Yemeni officials said another AQAP member on Yemen’s most-wanted terrorist list, Nasr al-Hotami of Rad`a, also was in the attacked pickup truck but had escaped. Al-Hotami is “a local bad guy” accused of killing a Yemeni security officer and two soldiers, the official said, adding that he did not have information that al-Hotami was involved in plots or attacks against the United States.[57]

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they were not aware of al-Hotami being in the procession and said they did not recognize his name. However, Iona Craig, a Sanaa-based journalist for the London Times who visited the strike area, said some witnesses told her that al-Hotami had been traveling in the attacked pickup truck. The witnesses said al-Hotami was known locally as a “brave man,” Craig said.[58]

Craig said the authorities had detained but released al-Hotami on suspicion of terrorism-related offenses against Yemeni targets in 2012, including the attack that killed the three security force members, and an 11-day takeover of Rad`a by AQAP in January of that year that ended when local tribes forced them out.[59] She also said she had not found any links between al-Hotami and activities against the United States.[60]

Three Yemeni officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that AQAP members had joined the procession, possibly as “camouflage.”[61] One of them said additional AQAP members may have been killed in the strike and their bodies removed by AQAP, but did not provide names or offer any information such as video footage or witnesses to support the claim.[62]

Abd al-Salam Muhammad, the Yemeni security analyst, told Human Rights Watch that he did not know if AQAP members were in the procession but that even if they were, three factors persuaded him that all 12 men killed were civilians.

The first factor, he said, was the contradiction between the official Yemeni statement of deaths and the provincial officials’ apology and payment of guns and money. The government statement’s omission of names of militants allegedly killed was striking, he said, given the authorities’ customary eagerness to name AQAP members they take out, while the guns and money were “a clear gesture of apology for wrongdoing.”[63]

Second, he said, AQAP did not describe any of those killed as “martyrs,” as it often—though not always—does when its fighters are killed. Third, he said, had those killed been known AQAP members, the families would not have displayed their bodies in Rad`a.[64]

Relatives Demand Redress

The relatives of the dead told Human Rights Watch that they did not consider the payment of money and guns from the Yemeni officials to be final compensation.

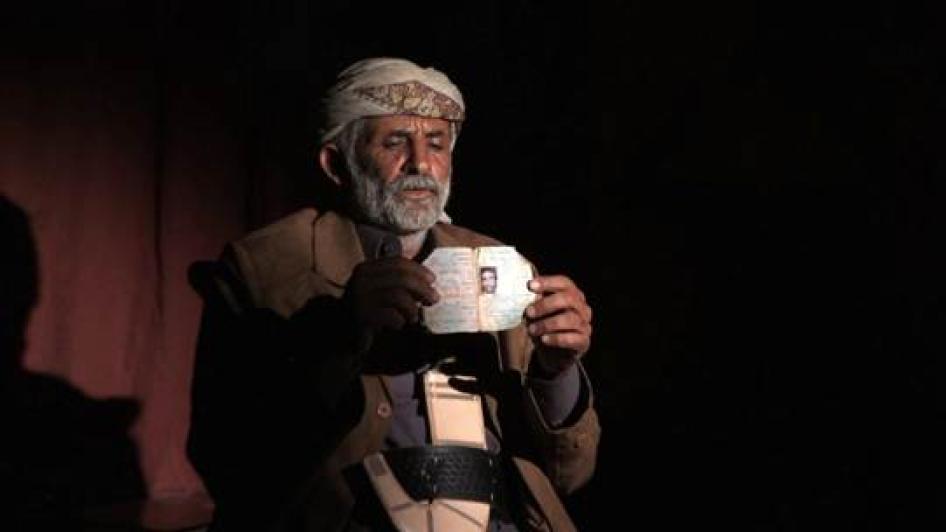

|

Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi of Yakla holds a photo of his son Ali Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, who was killed in a US drone strike outside Rad`a, Yemen on December 12, 2013. © 2013 Human Rights Watch |

“Our skies should be clear of these drones. We can’t lead our lives. We can’t sleep,” said Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, the local sheikh who lost his son. “After this attack, men, women, and children became more afraid; they are afraid of another strike. It has become a nightmare.”[65]

Three relatives warned of action by their powerful al-Qaifah tribal confederation if they did not see prosecutions and additional compensation. Abdu Rabu Abdullah al-Tisi, who lost four relatives in the strike, told Human Rights Watch: “If the government makes good on its word… then we’re okay. But our tribe is very big, and it will not forget the blood of our sons; it will not let this blood flow in vain.[66]

IV. International Law and US Policy

The Obama administration has repeatedly asserted that its program of targeted attacks fully comports with US and international law. [67] However, it has failed to provide a clear legal justification for targeted killings or respond to apparent violations of international law in individual attacks.

The lawfulness of a targeted killing hinges in part on the applicable international law, which is determined by the context in which the attack takes place. International humanitarian law, or the laws of war, is applicable during armed conflicts, whether between states or between a state and a non-state armed group. [68]

International human rights law is applicable at all times, but it may be superseded by the laws of war during armed conflict. Particularly relevant is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and authoritative standards such as the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials. [69]

In May 2013, amid mounting criticism of the US targeted killing program, President Obama outlined policy measures to limit civilian casualties during targeted attacks.

The following section briefly addresses the December 12 attack in Yemen in relation to these laws and policies.

Laws of War

The United States claims authority to carry out targeted killings as part of a war with Al-Qaeda and “associated forces”[70] such as AQAP. Should the hostilities between the United States and AQAP reach the level of an armed conflict, the laws of war govern these strikes in Yemen.

However, Human Rights Watch has questioned whether the laws of war apply to the fighting between the United States and AQAP in Yemen.[71]

Hostilities between a state and a non-state armed group are considered an armed conflict when fighting reaches a certain level of intensity and the armed group has the capacity and organization to abide by the laws of war.[72] This threshold is determined by the facts on the ground, not simply by the assertions of the parties.

While hostilities between AQAP and the Yemeni government have in recent years risen to the level of an armed conflict, it is not clear that those between AQAP and the US government meet this threshold. This distinction is important because the United States asserts it is not a party to the conflict between Yemen and AQAP.

Should the laws of war apply, they require that parties to an armed conflict distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians, and direct attacks only against combatants and other military objectives. Deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian objects are strictly prohibited.[73] Also prohibited are attacks that cannot or do not discriminate between combatants and civilians,[74] or in which the expected loss of civilian life or property is disproportionate to the anticipated military gain of the attack.[75] Therefore, not all attacks that cause civilian deaths violate the laws of war, only those that target civilians, are indiscriminate or cause disproportionate civilian loss.

Military objectives consist of combatants and “those objects which by their nature, location, or purpose make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage.” [76] Combatants include members of armed groups involved in military operations. [77]

In the conduct of military operations, warring parties must take constant care to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities, and are required to take precautionary measures with a view to minimizing incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects. These precautions include: doing everything feasible to verify that the objects to be attacked are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects [78] ; taking all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods of warfare to minimize loss of civilian life [79] ; and doing everything feasible to cancel or suspend an attack if it becomes apparent that a target is not a military objective or would result in disproportionate civilian loss. [80]

If an armed conflict exists between the United States and AQAP, members of AQAP involved in military operations would be valid targets. However even if the US targeted AQAP fighters who were valid military objectives during the attack on December 12, the lawfulness of the strike would depend on a number of additional factors, including whether the attack was carried out in a manner that could and did distinguish between combatants and civilians, and whether the attack could have been expected to cause disproportionate loss of civilian life or property.

The likelihood of civilian casualties from the December 12 strike raises concerns of a possible indiscriminate or disproportionate attack, but more information on the presence of AQAP fighters is needed to make that determination. Neither the US nor the Yemeni government has offered information to support their assertions that AQAP fighters were in the convoy at the time of the attack.

At the same time, if AQAP members deliberately deployed among civilians to deter an attack, they would be responsible for the serious laws-of-war violation of “human shielding.”[81] Any AQAP unlawful deployment among civilians would not, however, justify an indiscriminate or disproportionate attack by US forces.

One Yemeni official told Human Rights Watch that the participants in the procession had invited AQAP members to join them, suggesting that this made the participants valid targets of attack.[82] Even if true, civilians only become subject to deliberate attack if they directly participate in hostilities against the enemy, such as by loading weapons, spotting for artillery, or planning assaults, not indirectly assisting combatants or operations. In addition, “smugglers and arms dealers”—as one official characterized those killed—are also not directly participating in hostilities and thus not valid targets of military attack.

The US government has provided no information as to its legal basis for attacking the wedding procession. As is its practice, it has not released video from the drone that would shed light on the attack. There is also no indication that the US or Yemeni governments have conducted an investigation into possible violations of the laws of war in the December 12 attack.

International Human Rights Law

International human rights law protects the right to life. [83] Absent an armed conflict, international human rights law requires forces in operations against terrorist suspects to apply law enforcement standards. [84] These standards do not prohibit the use of lethal force, but limit its use to situations in which the loss of human life is imminent and less extreme means, such as capture or non-lethal incapacitation, would be insufficient. [85]

Under this standard, individuals cannot be targeted for lethal attack solely because of past unlawful behavior but only for posing imminent or other grave threats to life when arrest is not a reasonable possibility.

Human Rights Watch found no evidence, and the Obama administration has provided none, that the individuals taking part in the wedding procession posed an imminent threat to life. In the absence of an armed conflict, killings them would be a violation of international human rights law.

Obama Policy on Targeted Killings

In response to mounting calls for transparency about the US targeted killing program, President Obama on May 23, 2013 outlined steps that he said his administration takes or will take before targeting an individual for attack.[86] Even if the December 12 airstrike was a lawful attack on combatants in accordance with the laws of war, it is less clear that it met the May guidelines.

In broad terms, the standards unveiled in the president’s speech, and in accompanying documents including a White House Fact Sheet, suggest a policy that is reflective of international human rights law—setting a higher threshold for the use of lethal force than is required by the laws of war. [87]

These standards are:

- No Civilian Casualties. President Obama said that targeted strikes are only made when there is “near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured—the highest standard we can set.”[88]

- Ensure Target is Present. The White House Fact Sheet said there must be a “near-certainty” that the target is present.[89]

- Capture Target When Feasible. “Our preference is always to detain, interrogate, and prosecute” rather than kill, Obama said.[90]

- Target Must Pose an Imminent Threat. Obama said the United States only carries out strikes against those who pose a “continuing and imminent threat to the American people”—a legally ambiguous phrase—and does not target anyone to “punish” them for past deeds.[91]

The December 12, 2013 attack does not appear to meet these standards. In light of the apparent civilian casualties, possibly numerous, the US government should explain how it determined that there was a “near-certainty” of no civilian casualties. Moreover, if US forces were tracking al-Badani or al-Hotami, the government should explain why the attack could not have taken place before or after the wedding procession.

The US government also did not explain why those being targeted represented an imminent threat to the US. Finally, the United States never provided information as to why al-Hotami, if he was a target, could not have been captured, given that the Yemeni authorities had arrested him once before.

Obligation to Investigate, Provide Redress

States participating in an armed conflict have a duty to investigate allegations of serious laws-of-war violations.[92] A warring party also is obligated to provide redress for the loss or injury caused by violations of the laws of war.[93]

US authorities should officially acknowledge the December 12, 2013 strike and any investigation they are conducting into the apparent loss of civilian life. They should ensure this investigation is thorough, impartial, and transparent, and that it examines whether the strike contravened President Obama’s targeted killing policies as well as whether it violated international law.

The United States should discipline or prosecute those responsible if any violations are found. As US and NATO forces have done in Afghanistan, it should institute a system of condolence payments for all civilian casualties, in which there is no assumption of liability.

The Yemeni government, which permits the United States to carry out these strikes, should press the United States to conduct an investigation and facilitate the inquiry.

The United States should take similar steps for all other potentially unlawful killing operations it has carried out in Yemen. The only strikes the United States has officially acknowledged in Yemen since 2009 are the two that killed three Americans.[94]

By refusing to provide a public accounting of civilian casualties, the Obama administration is not only impeding the right of survivors and victims’ family members to seek redress for possible unlawful deaths. It also is sending the message that in the eyes of the United States, the hundreds of Yemenis killed in these strikes simply do not matter.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Letta Tayler, senior terrorism and counterterrorism researcher for Human Rights Watch.

It was edited by Andrea Prasow, senior national security counsel and advocate in the US Program of Human Rights Watch; Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of the Middle East and North Africa division; Tom Porteous, deputy program director; and James Ross, legal and policy director. Mark Hiznay, senior researcher in the arms division, reviewed references to weaponry, and verified ordnance and photographic evidence from the attacks. Robin Shulman, an editor in the Middle East and North Africa division, and Belkis Wille, Yemen researcher, provided regional review.

Kyle Hunter, associate in the emergencies division, and Jillian Slutzker, associate in the Middle East and North Africa division, provided production assistance. Kathy Mills, publications specialist; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, prepared the report for publication.

Human Rights Watch thanks the many witnesses, relatives of those killed, human rights organizations including Reprieve and the National Organization for Defending Rights and Freedoms (HOOD), and others whose assistance made this report possible.

[1] See, e.g., United Nations Human Rights Council, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Philip Alston, Addendum: Study on Targeted Killings,” May 28, 2010, A/HRC/14/24/Add.6, pp. 3-4 http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.24.Add6.pdf) (accessed February 9, 2014).

[2] See, e.g., The Long War Journal, “Charting the data for US air strikes in Yemen, 2002 – 2014,” http://www.longwarjournal.org/multimedia/Yemen/code/Yemen-strike.php (accessed January 28, 2014).

[3] See, e.g., Cora Currier, “Everything we know so far about drone strikes,” ProPublica, February 5, 2013. For more on JSOC, see Dana Priest and William M. Arkin, “‘Top Secret America’: A look at the military’s Joint Special Operations Command’,” Washington Post, September 4, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/top-secret-america-a-look-at-the-militarys-joint-special-operations-command/2011/08/30/gIQAvYuAxJ_story.html (accessed January 31, 2014). JSOC was reportedly responsible for the attack that killed Osama bin Laden in May 2011.

[4] The White House, Message to the Congress, Report Consistent with War Powers Resolution, 6-Month Report of December 13, 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/12/13/message-congress-report-consistent-war-powers-resolution (accessed January 28, 2014).

[5] Concerns about the US secrecy and inadequate legal rationale are set forth by Human Rights Watch and six other civil society organizations in their Joint letter to President Obama on Drone Strikes and Targeted Killings, December 5, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/12/05/joint-letter-president-obama-drone-strikes-and-targeted-killings.

[6] Human Rights Watch, “Between a Drone and Al-Qaeda,” October 2013, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2013/10/22/between-drone-and-al-qaeda-0.

[7] Ibid., chapters II, III. See also “Remarks by the President at the National Defense University” (Obama NDU Speech), May 23, 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/2013/05/23/remarks-president-national-defense-university (accessed January 28, 2013).

[8] See, e.g., Greg Miller, “In interview, Yemeni president acknowledges approving U.S. drone strikes,” Washington Post, September 29, 2012, http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-09-29/world/35497110_1_drone-strikes-drone-attacks-aqap (accessed January 10, 2014). See also UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, Ben Emmerson: Interim report to the General Assembly on the use of remotely piloted aircraft in counter-terrorism operations, A/68/389, September 18, 2013, para 52, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/478/77/PDF/N1347877.pdf?OpenElement (accessed February 12, 2014).

[9] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi, Sanaa, February 28, 2014.

[10] Human Rights Watch interviews with Yemeni Officials A and D, who spoke on condition of anonymity, January and February 2014.

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni official D, who spoke on condition of anonymity, February 2014.

[12] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni official B, who spoke on condition of anonymity, January 2014.

[13] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni official D, who spoke on condition of anonymity, February 2014.

[14] Human Rights Watch email exchange with US National Security Council spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden, February 14, 2014. See also Obama NDU Speech.

[15] Human Rights Watch email exchange with UK Foreign Office official who commented on condition of anonymity, February 17. 2014.

[16] Human Rights Watch email exchange with NATO official who commented on condition of anonymity, February 14, 2014.

[17] “Drone Strikes Must End, Yemen’s Parliament Says,” CNN.com, December 15, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2013/12/15/world/meast/yemen-drones/ (accessed December 15, 2013).

[18] This account is based on Human Rights Watch interviews with eight relatives of those killed in the strike, including two who were in the procession and witnessed the strike, as well as two journalists and two human rights defenders who visited the scene. The interviews were carried out between January 11 and 16, 2014 in Sanaa, and by telephone and email from New York, December 14, 2013, and January 27 to February 2, 2014.

[19] Ibid. Qat is a mild narcotic. Chewing qat is legal and a common pastime in Yemen.

[20] Two relatives, Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani and Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri, said a small number of women were in the procession in addition to the bride.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, Sanaa, January 11, 2014.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid. A senior Yemeni government official with knowledge of the attack, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he was informed that four men fled, but did not name them. Human Rights Watch interviews with a witness and a Yemeni government official, Sanaa, January 11-16, 2014.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Human Rights Watch interviews with eight relatives of those killed in the strike: Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi; Saleh Mohsen al- `Amri ; Abdu Rabu Abdullah al-Tisi; Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani; Talib Ahmad al-Tisi; Saleh Hussein Muhammad al- `Amri; and Aziz Mabkhut al-`Amry; all interviewed January 11, 2014, and Ali al-`Amri , interviewed by telephone from Sanaa to Rad`a, Human Rights Watch also confirmed this information with human rights defender Baraa Shaiban of Reprieve, Sanaa, January 11, 2014, and Yemeni journalist Nasser al-San`a, Sanaa, January 16, 2014, both of whom visited the scene.

[26]Greg Miller, “Lawmakers Seek to Stymie Plan to Shift Control of Drone Campaign from CIA to Pentagon,” Washington Post, January 15, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/lawmakers-seek-to-stymie-plan-to-shift-control-of-drone-campaign-from-cia-to-pentagon/2014/01/15/c0096b18-7e0e-11e3-9556-4a4bf7bcbd84_story.html (accessed January 15, 2014).

[27] See, e.g., “Soldier killed and another wounded in attack launched by unknown gunmen on security checkpoint in al Bayda,” al Masdar Online, January 31, 2014 (Ar). http://almasdaronline.com/article/54222(accessed February 2, 2014).

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with Muhammad Abdullah al-Tisi, Sanaa, January 11, 2014.

[29] Ali Abdullah al-Tisi was buried in his home village of Jishm Yakla, his father told Human Rights Watch.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani, Sanaa, January 11, 2014.

[31] Human Rights Watch interview with Nasser al-San`a, Sanaa, January 16, 2014.

[32] Human Rights Watch interviews with relative Abdu Rabu Abdullah al-Tisi, Sanaa, January 11, 2014, and al-San`a, Sanaa, January 16, 2014.

[33] Video of Abdullah Mabkhut al-`Amri, copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[34] Human Rights Watch interviews with relatives and government officials. See also “Yemen tribe intensifies protest against drone attacks,” Oman Tribune, December 14, 2013, http://www.omantribune.com/index.php?page=news&id=157492&heading=Middle%20East (accessed February 2, 2014).

[35] Video of demonstration in Rad`a, December 13, 2013. Copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

[36] The dead were identified by relatives Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi; Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri; Abdu Rabu Abdullah al-Tisi; Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani; Talib Ahmad al-Tisi; Saleh Hussein Muhammad al-`Amri ; and Aziz Mabkhut al-`Amri; all interviewed January 11, 2014, and Ali al-`Amri, interviewed by telephone from Sanaa to Rad`a, February 2, 2014. Many of the ages are approximate, as Yemenis often do not have birth records and not all relatives were certain of birth dates.

[37] Names and conditions of the wounded provided by Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani, who received the injured at the hospital; Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri; and journalists who visited the scene, January 11 and February 2, 2014.

[38] Kimberly Dozier, “US officials: drone targeted embassy plot leader,” AP, December 20, 2013, http://bigstory.ap.org/article/us-officials-drone-targeted-embassy-plot-leader (accessed December 20, 2013).

[39] Ibid.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni government official, January 2014. Further details withheld, and telephone interview with Abd al-Salam Muhammad, New York to Sanaa, February 4, 2014.

[41] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Muhammad, February 4, 2014.

[42] Michael Isikoff, “US investigates Yemenis’ charge that drone strike ‘turned wedding into a funeral,’ ” NBC News, January 7, 2014, http://investigations.nbcnews.com/_news/2014/01/07/22163872-us-investigates-yemenis-charge-that-drone-strike-turned-wedding-into-a-funeral?lite (accessed January 7, 2014).

[43] See, e.g., Mark Mazzetti and Robert F. Worth, Yemen Deaths Test Claims of New Drone Policy, New York Times, December 20, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/21/world/middleeast/yemen-deaths-raise-questions-on-new-drone-policy.html (accessed December 20, 2013).

[44] Email from US National Security Council spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden to Human Rights Watch, February 3, 2014.

[45] Ibid.

[46] US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Nomination of John O. Brennan to be the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Responses to Post-Hearing Questions, February 16, 2013, http://www.intelligence.senate.gov/130207/posthearing.pdf (accessed June 11, 2013).

[47] “Supreme Security Committee source: air strike targeted a car belonging to one of the leaders of al-Qaeda” (Ar), Saba News, December 13, 2013, http://www.sabanews.net/ar/news334625.htm (accessed January 26, 2014). See also “Yemen Airstrike Targeted Al Qaeda Militants,” Associated Press, December 13, 2013, http://www.businessweek.com/ap/2013-12-13/yemen-airstrike-targeted-al-qaida-militants (accessed December 13, 2013).

[48] Human Rights Watch interviews with Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri, January 11, 2014; San`a, January 16, 2014; Ali al-`Amri, a councilman from al-Baida; February 2, 2014, all of whom were present at the meeting. The apology and gift of assault rifles also was widely reported in Yemeni media. See, e.g., “Government Offers Guns and Money to Families of Those Killed in Al-Beida,” Yemen Times, December 17, 2013, http://www.yementimes.com/en/1738/news/3238/Government-offers-guns-and-money-to-families-of-those-killed-in-Al-Beida%E2%80%99a-airstrike.htm (accessed January 26, 2014).

[49] Human Rights Watch interviews with Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri, January 11, 2014, and San`a, January 16, 2014, both of whom were present at the meeting, as well as Ali al-`Amri, a councilman from al-Baida who was involved in mediations between the family and the government, January 16 and February 2, 2014.

[50] Human Rights Watch interviews with seven relatives of the dead, January 11, 2014.

[51] Human Rights Watch interviews with Saleh Mohsen al-`Amri, January 11, 2014; San`a, January 16, 2014, and Ali al-`Amri, February 14, 2014. See also, e.g., “Government Offers Guns and Money to Families of Those Killed in Al-Beida,” Yemen Times, December 17, 2013, http://www.yementimes.com/en/1738/news/3238/Government-offers-guns-and-money-to-families-of-those-killed-in-Al-Beida%E2%80%99a-airstrike.htm (accessed January 26, 2014).

[52] Human Rights Watch interviews with the former Yemeni official, Official A, as well as current Yemeni Officials B and D, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with Official A. Further details withheld.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Yemeni Official D, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[55] Human Rights Watch interviews with Officials B and D, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[56] Human Rights Watch interview with Ahmad Muhammad al-Salmani, January 11, 2014.

[57] Human Rights Watch interview with Official D, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[58] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Iona Craig from New York to Sanaa, January 27, 2014. See also Craig, “What really happened when a U.S. drone hit a Yemeni wedding convoy,” Aljazeera America, January 20, 2014, http://america.aljazeera.com/watch/shows/america-tonight/america-tonight-blog/2014/1/17/what-really-happenedwhenausdronehitayemeniweddingconvoy.html (accessed January 20, 2014).

[59] See, e.g., Erwin van Veen, “Al-Qaeda in Radaa, Yemen – global security challenge or local succession dispute?” Global Coalition for Conflict Transformation, February 5, 2014, http://www.transconflict.com/2014/02/al-qaeda-radaa-yemen-global-security-challenge-local-succession-dispute-502/ (accessed February 8, 2014).

[60] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with journalist Iona Craig, New York to Sanaa, January 27, 2014.

[61] Human Rights Watch interviews with Officials A, B and D, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[62] Human Rights Watch interview with Official B, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[63] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Muhammad, February 4, 2014.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Human Rights Watch interview with Abdullah Muhammad al-Tisi, January 11, 2014.

[66] Human Rights Watch interview with Abdu Rabu Abdullah al-Tisi, January 11, 2014.

[67] See, e.g., Jeh Johnson, “National Security Law, Lawyers and Lawyering in the Obama Administration” (Johnson Speech), Yale Law School, February 22, 2012, available at http://www.cfr.org/national-security-and-defense/jeh-johnsons-speech-national-security-law- lawyers-lawyering-obama-administration/p27448 (“We must apply, and we have applied, the law of armed conflict, including applicable provisions of the Geneva Conventions and customary international law, core principles of distinction and proportionality, historic precedent, and traditional principles of statutory construction.”).

[68] The laws of war can be found, for example, in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their two Additional Protocols; the 1907 Hague Regulations; and the customary laws of war.

[69] See International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), G.A. res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force Mar. 23, 1976 (the US became a party to the ICCPR in 1992); UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, Havana, 27 August to 7 September 1990, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.144/28/Rev.1 at 112 (1990).

[70] See, e.g., Johnson Speech, February 22, 2012, http://www.cfr.org/national-security-anddefense/jeh-johnsons-speech-national-security-law-lawyers-lawyering-obama-administration/p27448, and Attorney General Eric Holder, “Remarks at Northwestern University School of Law,” March 5, 2012,http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/ag/speeches/2012/ag-speech-1203051.html (accessed January 29, 2014).

[71] Human Rights Watch, “Between a Drone and Al Qaeda,” pp. 92-93; see also Human Rights Watch, Letter to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel on Reassessing the Al-Qaeda War Model, July 29, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/07/29/letter-defense-secretary-chuck-hagel-reassessing-al-qaeda-war-model.

[72] See International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), “How is the Term ‘Armed Conflict’ Defined in International Humanitarian Law?” March 2008, p. 3, http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/opinion-paper-armed-conflict.pdf.

[73] International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Henckaerts & Doswald-Beck, eds., Customary International Humanitarian Law (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press 2005), rule 1, citing Protocol II, art. 13(2).

[74] Ibid., chapter 3, citing Protocol I, art. 51(4).

[75] Ibid., chapter 4, citing Protocol I, art. 57.

[76] Ibid., rule 8, citing Protocol I, arts. 48, 51(2), and 52(2).

[77] Ibid., rule 6,citing Protocol II, art. 13(3).

[78] Ibid., rule 16, citing Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a).

[79] Ibid., rule 17, citing Protocol I, art. 57(2)(a).

[80] Ibid., rule 18, citing Protocol I, art. 57(2)(b).

[81] Ibid., citing Protocol I, art. 51(7).

[82] Human Rights watch interview with Official B, January 2014. Further details withheld.

[83] See ICCPR , art. 6.

[84] The application of human rights law in situations outside an armed conflict is consistent with the rulings of the International Court of Justice in its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Nuclear Weapons), http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/95/7495.pdf, and its2004 Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (The Wall), http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/131/1671.pdf.

[85] See UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, principle 9.

[86] “Remarks by the President at the National Defense University,” May 23, 2013, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/05/23/remarks-president-national-defense-university (accessed May 23, 2013).

[87] Obama NDU Speech, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/2013/05/23/remarks-president-national-defense-university. Along with the speech, the White House released a Fact Sheet “summarizing” a classified Presidential Policy Guidance on targeted killings that Obama had signed one day earlier.. The White House, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Policy Standards and Procedures for the Use of Force in Counterterrorism Operations Outside the United States and Areas of Active Hostilities” (Targeted Killing Fact Sheet), May 23, 2013, www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/2013.05.23_fact_sheet_on_ppg.pdf (accessed February 10, 2014).

[88] Obama NDU Speech.

[89] Targeted Killing Fact Sheet.

[90] Obama NDU Speech.

[91] Ibid.

[92] ICRC, Customary International Humanitarian Law, rule 158, citing, e.g., Fourth Geneva Convention, art. 146.

[93] Ibid., rule 150.

[94] The three Americans were Anwar al-Awlaki, a cleric whom the United States alleged was an AQAP leader; Abd al-Rahman al-Awlaki, al-Awlaki’s teenage son, who the US says was not a target; and Samir Khan, the editor of the AQAP magazine Inspire.